With hopes of return fading, migrants are slipping into debt trap: Study

“About 85% of the returnee migrants expressed their need for loans to either rehabilitate or to go abroad”

Shahin Alam has a work permit in Malaysia and his employer is asking him to return to work. But he doubts he will be able to travel before his visa expires on 16 January as migrant workers are still not allowed to enter Malaysia due to Covid-19.

He arrived home in February on leave after a 6-and-half-year stay in Malaysia. “I was supposed to return after four months, but now I have got stuck. If I knew this could happen, I would never have thought of coming to Bangladesh,” says Shahin from Jashore.

Shahin is among those migrant workers who came home on leave and are now in fear of losing jobs as the persisting pandemic has made their return uncertain. Shahin has now bought a battery-run autorickshaw with the money he could save to earn a living.

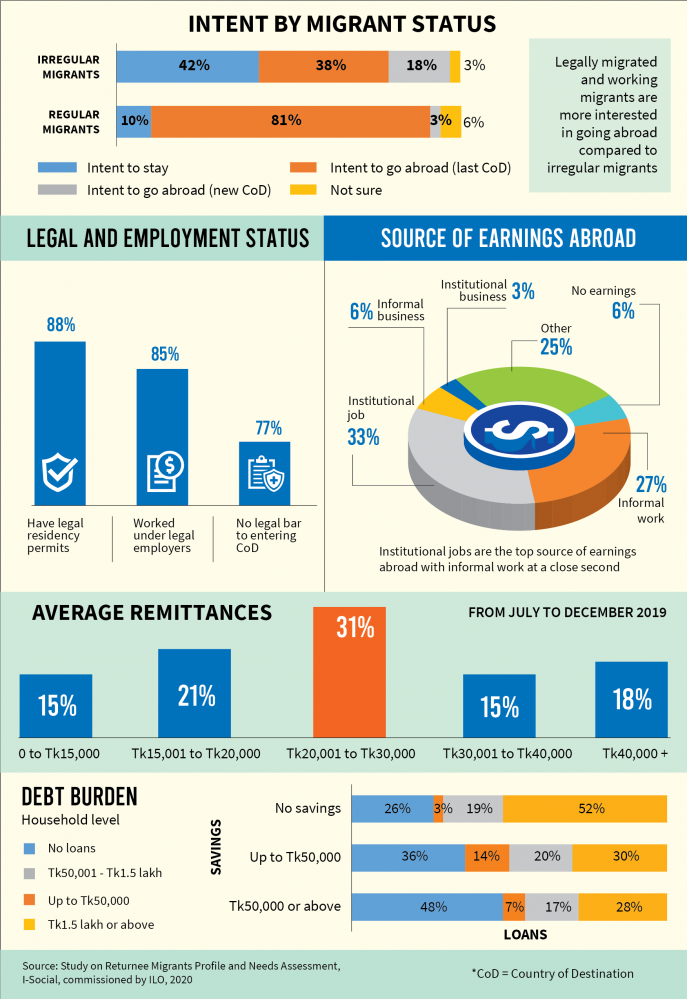

According to a study, more than 80% of the returnee migrant workers want to go back to work abroad but got stuck due to the pandemic.

Most of them have already exhausted their savings, while some became indebted afresh to meet family expenditures during months of stay at home with no income.

About 85% of the returnee migrants expressed their need for loans to either rehabilitate in the country or to go abroad, reveals the study of iSocial, a research organisation.

The study named Returnee Migrants Profile and Needs Assessment, commissioned by the ILO Bangladesh and funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), is intended to help the expatriates’ welfare ministry develop a post-pandemic roadmap for migrant workers.

It surveyed 616 migrant workers of Cumilla, Munshiganj, Jashore and Brahmanbaria who have returned since January 2020. To ensure a minimum representation of female returnee migrants, the survey coverage was extended to few other districts.

Most of these migrants (85%) have stated that remittance is the main source of their household income and they need to go back. Only one in five of the returnee migrants have more than Tk50,000 as household savings, while more than a half of them reported taking loans exceeding Tk1 lakh after coming to Bangladesh.

Mohammad Sobuj spent Tk3 lakh to go to Oman two years ago and repaid half of the amount. But he had to take loans from NGOs to run his six-member family, forget about repaying past loans. He had come home two weeks before the first coronavirus case was detected in Bangladesh in March and was scheduled to go back in one and a half months.

“My owner still wants me to go back, but my visa has already expired. Now I am in serious hardship, I cannot explain it to you in words,” says Sobuj from Chouddagram upazila of Cumilla.

Even if he manages to get the visa and work permits renewed, he will have to struggle for loans to buy an air ticket.

The study finds 85% of respondents are in need for loans, either to stay back or to go abroad.

“This is not surprising because Bangladeshi migrants tend to be among the lowest paid migrants and many have lost jobs and other income opportunities due to the pandemic,” it reads.

Safety-net coverage was also low for migrants and their families in distress. Only around 4% of households received support under the social help programme.

Of the surveyed, two-thirds returned from the Gulf countries and the rest from Southeast Asia. More returnees from Southeast Asia, mainly Malaysia and Singapore, want to return to their previous destinations than those willing to go back to the Middle East, meaning that job uncertainty is higher in Gulf countries, the study points out.

Among the respondents, 4.5% are female, whose condition was more shocking.

Ayra Khatun and her daughter Sharmin were among a batch of workers brought back home from Saudi Arabia by a return Hajj flight in April under government arrangement.

“They beat me and left me outside the home,” she said over mobile phone from her village home in Sharsha, Jashore. She was rescued by her daughter’s employer and taken to hospital before being sent to jail.

She could not speak more as she was suffering from neurological problems. Her husband narrated the horrific tales of her work in Saudi Arabia as a domestic help. “The employer was so bad, they seized her passport and mobile SIM card. They did not take her to hospital when she fell ill after their beating,” said Babor Ali over the phone, crying.

He had to send Tk50,000 to pay the hospital bill for Ayra Khatun’s treatment and process paper for her return.

The incomes of his wife and daughter prompted Babor to start building a new brick house. But the two had to return before the work completed. “Now I owe money to the rod-cement shop. I borrowed money from Brac for the treatment of my wife.”

His daughter Sharmin was well under a good employer, but Babor would not send her again. He wants to do something here to feed the family. “I thought of cattle farming, but I have no money to start with,” he said.

He does not know where he will get Tk7 lakh to repay debt, take his wife to doctor in Dhaka and then buy cows to rear.

About 66% of the migrants returned home empty-handed and with little or no savings; they are more likely to slip into debt traps, the study hints.

![]()