Climate Migration in Bangladesh: A Ride through Hope and Despair

Author: Niloy Sarker

Bangladesh is known across the world as the land of rivers. With about 800 rivers crisscrossing the land mass, it is one of the most fertile countries in the world (Zaman, 1993). The people of the land have always enjoyed agricultural and natural abundance.

Our connection with nature has been a great kinship mostly of favor and kindness yet often of ruthless natural calamity in the form of floods, cyclones, drought, etc. (Akhter et al., 2015). The geographical disposition of Bangladesh has always made its people vulnerable to natural disasters and this feat has been worsened with the increasing impact of climate change. Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to several natural hazards, such as floods, droughts, cyclones, and earthquakes due to its flat topography, low-lying environment, and socioeconomic environment (Lein & Lein, 2000).

As the world is beginning to feel the full-fledged force of climate change Bangladesh and its people are faced with challenges of greater diversity and proportions. Research shows that people affected by climate change are leaving behind their homelands and moving out toward cities in search of better livelihood and safety.

Natural Disasters in Bangladesh and the Effect of Climate Change.

By 2050, it is predicted that 17% of the nation’s coastal regions will be underwater, displacing roughly 20 million people (Climate Impact on Country’s Coastal Region: 13.3 Million at Risk of Displacement by 2050 | The Daily Star, 2021). According to the Global Climate Risk Index 2020, Bangladesh was listed as the seventh riskiest country(Eckstein et al., 2019).

70% of Bangladesh experiences flooding every year as the country is a landmass of low-lying flood plains. In 2022, the northeastern regions of Sylhet, Sunamganj, and Netrokona faced one of the worst floods in the history of the land affecting more than 7.2 million people(Shafiq, 2023).

In Bangladesh, 20 out of the 64 districts are vulnerable to riverbank erosion, which consumes 8700 ha of land annually and impacts 200 000 people by destroying their homes and/or agricultural lands(Freihardt & Frey, 2023). Riverbanks are eroded by the strong gushing river waters destroying habitats in the rural region because of which millions have lost their homes and livelihoods.

The districts with the highest risk of erosion, according to the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), are Bogra, Sirajganj, Kurigram, Lalmonirhat, Gaibandha, and Rangpur in the nation’s north; Chandpur, Manikganj, Rajbari Shariatpur, and Faridpur in the Dhaka zone; Tangail and Jamalpur in the Mymensingh zone; and the coastal regions of Patuakhali(Disaster Summary Sheet: Bangladesh – Riverbank Erosion – Bangladesh | ReliefWeb,2019).

The rise in sea level due to global warming causes coastal region flooding which consequently leads to increased salinity in these regions affecting the supply of freshwater that is vital for survival and irrigation.

According to research, Chittagong and Khulna districts are projected to experience the highest levels of extra migration within the districts, with an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 migrants moving there annually due to salinity which is estimated to rise by 55% in these areas(Chen & Mueller, 2018).

Nearly every year, cyclones strike Bangladesh’s coastal regions, with winds reaching up to 220 km/h and tidal ranges up to 3 m high that may rise to 7 m further west at the mouth of the Meghna Estuary, to the east of Bhola. In the Bay of Bengal, cyclone season primarily occurs between April and May and October and November, before and after the monsoon season. The districts that are most severely impacted by cyclones are Khulna, Patuakhali, Barisal, Noakhali, and Chittagong. Some of the most devastating cyclones experienced by the region are the Bhola Cyclone of 1970, the 1991 cyclone, Sidr2007 and Aila of 2009

With the rise of sea level, the sea surface temperature changes and this increases the intensity of tropical cyclones that are prominent in the delta regions(Knutson et al., 2019). Stronger cyclones would mean more loss of life and property.

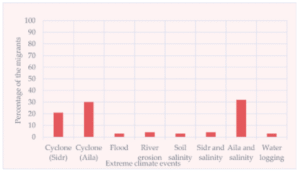

In a desperate attempt to cope with the disasters the victims of natural disasters induced by climate change migrate to the cities to find work and shelter.

(Ahsan, 2019b) Migration trend due to extreme climate events from 1980 to 2010

A Move Towards Hope; Push and Pull Factors of Migration

Those who are compelled to leave their homes either permanently or temporarily due to a sudden onset of the climate-related catastrophic event are said to be displaced due to the climate migration brought on by climate change is more complicated, with the choice to relocate frequently influenced by several factors (such as risk from climate change and slow-onset climate catastrophes) and, to some extent, voluntarily. It might be challenging to distinguish between displacement and migration. Climate migration is the term we use to describe both.

People move for a variety of reasons, such as raising their standard of living, diversifying their sources of income, and adjusting to environmental and climatic changes (Martin et al., 2014). When perceived environmental change and climate variability are present, migration is viewed as socially acceptable behavior. According to Martin (2014) when making decisions about where to go, when to go, and what to do for a career, people frequently rely on information from their social networks. Despite all the risks involved, migration is not viewed as a pioneering or risk-taking endeavor, but rather as a routine practice.

In most cases, male working members of the family failing to find sustainable work in the disaster-affected areas of their village move out towards the cities leaving behind the female, children, and elderly members of the family. People move out of their native land because of either of the four reasons (Ahsan et al., 2016).

- They have lost everything in their origin land- 50.9%

- Do not have much hope to start fresh livelihood in their disaster-affected homeland- 34.5%

- They want to keep their family safe from climate hazards- 0.9%

- Hope to have a better life and livelihood in the cities 13.6%

Once an area is affected by a natural disaster such as cyclone, flood, or river erosion the resources available in the area cease to be sufficient to support its population. In addition, the means of income is also lost. For example, after Sidr and Aila hit the coastal regions of Bangladesh farmers lost their agricultural lands, fish and crab farms(Islam et al., 2020). The people of these rural areas are double victimized as they had already been living in conditions of poverty, lack of education, and lack of diverse employment opportunities

Safe Shelter: The primary reason for people to come to urban centers is to look for shelter or housing that is safe from natural disasters. They also find homes in and around the urban poor settlements that are comparatively cheaper to settle in.

Economic Stability: The victims of climate change often seek sources of income to support their families back in the village or the new urban settlements. As they can no longer access their traditional occupation like fishing, farming, or cattle rearing these men and women look for alternative jobs in the cities. The migrants from the rural areas believed they had the skills to get jobs in the city’s industrial sectors.

Access to health, education, and other necessities: While there are many reasons for migration the individuals who choose to or are forced to migrate from an area affected by climate change are often than not looking for better health, education, and other public services and basic rights that they would have otherwise enjoyed in their origin.

Unforgiving Reality Faced by the Climate Migrants

Often the expectations of having access to a better life and livelihood in the cities are not met. Once the people have migrated to the cities, they face a series of harsh realities that make their already miserable life even harder.

Lack of access to basic services such as shelter, water, sanitation, and healthcare

Losing all they had, the climate migrants from rural regions of the country move towards the cities in search of better means of livelihood and shelter (Shahid Sams, 2019). However, the most vulnerable poor population can only manage housing in and around the poor urban areas that are in high-risk ecological zones.

Many migrant communities have no choice but to settle as squatters in urban fringe areas, on marginal agricultural land, along rail corridors, next to the highway, or even in the natural drainage network, as well as in low-lying flood-prone areas and on riverbanks, using various methods, including sloppy building supplies ((Ahsan, 2019a). Some of those migrants received quick shelter in these different types of informal communities, but they were unable to receive social security and justice in an urban setting.

In the urban settlements of Khulna, Dhaka, or Chittagong where the migrants settle down there is hardly any clean water to drink or proper sanitation facilities. Besides, waste management is extremely poor which increases the chance of several communicable diseases among the inhabitants. Poor sanitation, waste management, and dirty and shared kitchen and bathrooms pose severe health hazards for the already vulnerable people.

Eviction and security threats from the authorities and leaders

Musclemen or powerful leaders often threaten the migrants to leave the slum areas if a certain amount of toll is not paid (Ahsan, 2019a). This put an extra financial and security burden on the already victimized migrants. Three-fourths of the climate migrants live with the fear of eviction or abuse (Adri, 2014). There is a fear that local goons will evict them out of their residents. Often vulnerable migrants such as children, the elderly, and women are evicted into the open without any consideration of their age or gender sensitivity. Women in every regard face double victimization due to climate migration concerning security, safety, healthcare, etc. (Khanom et al., 2022).

Limited employment opportunities and low wages

The migrants in their land of origin were involved in various traditional occupations that suited the climate, environment, and nature of their rural villages. In the urban cities, they are forced to choose completely different modes of earning with they have little or no acquaintance. For instance, they used to be farmers, seasonal employees, and small company owners but were suddenly made to work as day laborers. Many of them are unfamiliar with metropolitan life, income and living standards, and sophisticated urban systems(Ahsan, 2019). That put them on the brink of vulnerability at a time when they are already vulnerable due to being uprooted from their place of origin.

They travel to locations where they can work as rickshaw or van pullers, construction laborers, ship breakers, or any other type of day labor, depending on their talents and experience. As a result, the displaced men struggle to fit into the metropolitan social system.

Most of the time, blue-collar migrant workers’ positions are temporary. For informal jobs, there is stiff competition and little remuneration. Since they lack social networks and job contracts, migrants are more at risk of losing their ability to enforce their labor rights(Shahid Sams, 2019).

It makes it harder for them to acquire enough money to support their livelihoods. Male and female migrants with lower levels of education have reduced access to jobs in the white-collar sector. As a result, they push blue-collar workers to labor in unofficial areas.

Discrimination and social exclusion from the local urban society

The rural migrants who come to live in the slums of urban areas are seen as distinct from the established community in their new urban setting and as having a lesser social rank than the rest of the community.

These poor victims of climate change chose to relocate to areas with affordable land and convenient access to employment because they have already lost everything in their homeland. For many, this meant squatting illegally on government-owned property, such as railway or highway verges, or agricultural land on the outskirts of cities, frequently in subpar temporary housing(Ahsan & Afrin, 2019).

While there is a risk of eviction there is also the sense of moving down in the social status among these people, many of whom had owned land and property once upon a time. Even though many migrants live in the slums and outskirts for a longer time they are rarely accepted in the local urban society. This creates a sense of frustration and lowliness among the climate migrants.

Besides these, there is a persistent risk of conflict with the host community over the use of limited resources. The struggle to access food, water, health, education, and other basic services is never-ending. Often locals take advantage of the uneducated and unskilled rural migrants and abuse them in various ways. These migrants have no legal identities in the cities and thus are vulnerable to crimes such as trafficking, physical abuse, and kidnapping. Members of the migrant communities have to offer services and appease the local authorities to continue their residence in the slums, and this often takes extreme turns where there is a violation of human rights and dignity.

The devastated migrants have no way to go back to their villages and have the sustained life they once had. The nature that once gave them all they needed had rudely turned against them for little or no fault of theirs. Yet, in their instinct to live on as all living beings do, they have made a move to the cities with the hope that somehow, someday someone shall make a change. They live in despair, yet they live in hope that one day everything will be all right again. We must implement policies and take steps to address their special needs so that if not many at least their basic human rights are respected.

Bibliography

Adri, N. (2014). Climate-induced Rural-Urban Migration in Bangladesh : Experience of Migrants in Dhaka City. 1–335. https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=4&uin=uk.bl.ethos.792335

Ahsan, R. (2019a). Climate-Induced Migration: Impacts on Social Structures and Justice in Bangladesh. South Asia Research, 39(2), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0262728019842968

Ahsan, R. (2019b). Climate Change and Uncharted Social Challenge in Existing Urban Setup in Bangladesh. In Climate Change and Agriculture: Vol. i (Issue tourism, p. 13). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.83409

Ahsan, R., & Afrin, S. (2019). Understanding Climate-Induced Migration: Bangladesh a Place to Explore the Reality. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 54(5), 702–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909619839420

Ahsan, R., Kellett, J., & Karuppannan, S. (2016). Climate Migration and Urban Changes in Bangladesh. In Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802169-9.00019-7

Akhter, S. R., Sarkar, R. K., Dutta, M., Khanom, R., Akter, N., Chowdhury, M. R., & Sultan, M. (2015). Issues with families and children in a disaster context: A qualitative perspective from rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 13, 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJDRR.2015.07.011

Chen, J., & Mueller, V. (2018). Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nature Climate Change 2018 8:11, 8(11), 981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0313-8

Climate Impact on Country’s Coastal Region: 13.3 million at risk of displacement by 2050 | The Daily Star. (2021). The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/environment/climate-change/news/climate-impact-bangladesh-133-million-risk-displacement-2050-2176031

Eckstein, D., Vera, K., & Schafer, L. (2019). GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2020. In Germanwatch e.V. (Issue March).

Freihardt, J., & Frey, O. (2023). Assessing riverbank erosion in Bangladesh using time series of Sentinel-1 radar imagery in the Google Earth Engine. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 23(2), 751–770. https://doi.org/10.5194/NHESS-23-751-2023

Islam, M., Jamil, M., Chowdhury, M., Kabir, M., & Rimi, R. (2020). Impacts of cyclone and flood on crop and fish production in disaster prone coastal Bhola district of Bangladesh. International Journal of Agricultural Research, Innovation and Technology, 10(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.3329/ijarit.v10i1.48093

Khanom, S., Tanjeela, M., & Rutherford, S. (2022). Climate-induced migrant’s hopeful journey toward security: Pushing the boundaries of gendered vulnerability and adaptability in Bangladesh. Frontiers in Climate, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.922504

Knutson, T., Camargo, S. J., Chan, J. C. L., Emanuel, K., Ho, C. H., Kossin, J., Mohapatra, M., Satoh, M., Sugi, M., Walsh, K., & Wu, L. (2019). Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100(10), 1987–2007. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0189.1

Lein, H., & Lein, H. L. (2000). Hazards and “forced” migration in Bangladesh. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography, 54(3), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/002919500423735

Martin, M., Billah, M., Siddiqui, T., Abrar, C., Black, R., & Kniveton, D. (2014). Climate-related migration in rural Bangladesh: A behavioural model. Population and Environment, 36(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0207-2

Shafiq, S. I. (2023). THE FREQUENCY AND IMPACT OF FLOODING IN THE SYLHET DIVISION OF BANGLADESH: AN INVESTIGATION. International Journal of Business, Social and Scientific Research, 11(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.55706/IJBSSR11103

Shahid Sams, I. (2019). Climate Induced Migration and Social Mobility Among Migrants: Evidence from the Southwest Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Social Sciences, 8(4), 147. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20190804.12

Web, R. (2019). Disaster Summary Sheet: Bangladesh – Riverbank Erosion (21 March 2019) – Bangladesh | ReliefWeb. OCHA. https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/disaster-summary-sheet-bangladesh-riverbank-erosion-21-march-2019

Zaman, M. Q. (1993). Rivers of Life: Living with Floods in Bangladesh. Asian Survey, 33(10), 985–996. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645097