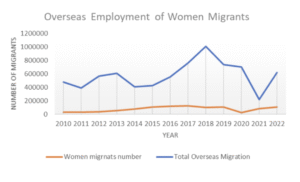

In Bangladesh, women started participating in labour migration since 1991, and as of December 2022, a total of around 1.11 million women migrant workers have gone abroad, which is around 7.5% of total labour migration from Bangladesh so far[BMET 2022]. Saudi Arabia is the major destination for women migrant workers. The other destination countries include United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Oman, Lebanon, Qatar, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore. The women migrant workers mostly work as domestic help in the destination countries. Other than domestic work, women workers from Bangladesh are also contributing as Garment factory workers, Caregivers, Nurses, and Cleaners. Women participation in overseas employment makes Bangladesh the 6th largest migrant-sending country globally and the 7th largest remittance-receiving country [World Bank 2022].

Depending on the channels availed by an aspirant woman migrant, labour migration from Bangladesh takes several different paths. In Bangladesh, the risks and challenges faced by women migrant workers can be categorized into different steps of the labour migration journey. There are 14 broad steps in a labour migration journey for a woman [Figure 1, 2, and 3], and in each of these steps there are multiple scenarios , where each scenario poses various degrees of risks, ranging from ‘safe’ [deep green] to ‘high risks’ [red], which are presented in the Figures, where two other risk levels : ‘low risk’ [blue] and moderate risk [brown] are also presented.

Step 1. Getting Information and Decision Making

Getting information and decision-making largely determines the subsequent risks and challenges a woman migrant worker may face. In this step, access to information at various stages of decision-making plays a very important role.

It all starts with a discussion within the family and then gradually getting more specific information about specific scope through one of the many channels like newspapers, websites, family members, relatives and acquaintances, and other migrant workers’ families. In certain cases, decision-making happens within the family or solely by the aspirant woman migrant workers themselves. In this very step, informal intermediaries, which are both connected to a private recruitment agency (PRA) and independent ones, play a major role, as they are known within the community and are familiar with the good practices or bad practices, depending on their interests. Additionally, Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) play an important role in making information available for the aspirants and their families; however, their spread and consistency vary. Women’s decision making needs to be facilitated by the relevant agencies, where social norms and cultural issues need to be addressed.

Step 2. Choice of Channel for Labour Migration

In labour migration, there are various channels that individuals can turn to for information and support. For women migrant workers, the most common channels include self-research, seeking advice from family and friends, and reaching out to the District Employment and Manpower Office (DEMO).

While all of these channels can be helpful in providing information and guidance, DEMO stands out as the safest option for women migrant workers. This is because DEMO can offer reliable and accurate information on labour migration procedures, job opportunities, and working conditions, while also ensuring that women are protected from potential risks and exploitation.

However, the choice is also made for an informal intermediary which is the riskiest but remains lucrative as this channel appears as the biggest support for a woman who is distressed by push factors within the family (domestic violence or abuse, lack of opportunities for education or employment, financial difficulties, and conflicts with family members, etc.).This step is associated with challenges and risks like financial detriment and fraud. There is also a serious threat of legal actions taken against the migrant due to using unlawful requirement methods.

Step 3. Getting Recruited

This is the most important step in the whole labour migration journey of a woman. There are three safe or low-risk ways to be recruited: directly by the employer or its representatives, directly by the PRA facilitated by DEMO/ Bureau of Manpower, Employment, and Training (BMET) /NGO, and, directly by a PRA. Moving more towards the riskier channels, being recruited through an informal intermediary (connected to PRA) holds moderate risk, whereas recruitment through an independent informal intermediary carries the highest risk. Due to choosing the wrong channel, a woman migrant worker becomes subject to having false recruitment papers leading to being forcibly in unscrupulous jobs with no minimum wage guaranteed or benefits ensured. In many cases, the woman migrant worker chooses to go as a wife or girlfriend with a visit visa through a middleman.

Step 4. Getting NID and Passport

It is rare where a woman migrant worker herself chooses to get NID and passport. The low-risk mediums for availing these documents are self, and, family and friends. The moderately risky medium is an informal intermediary connected to a PRA and the high-risk medium is the independent informal intermediary. There is no ‘safe’ medium here as in the majority of cases, the woman migrant workers are forced to pay other intermediaries connected to the passport office. In certain cases, they receive a false NID or passport. Associated risks, issues, and challenges in this step include receiving false documents, and financial losses.

Step 5. Visa Processing

Generally, in this step, a combination of two of the mediums is used with the direct presence of the aspirant woman migrant worker: family and friends with low risk, and, an informal intermediary connected to a PRA with moderate risk, associated with monetary damages. Sometimes, NGOs also assist in getting visas. Out of all the mediums, by choosing the independent informal intermediary, the aspirant falls for the riskiest channel as there is a chance of getting a false visa document, which may lead to arrest, imprisonment, and deportation.

Step 6. Medical Check-up

The medical check-up is a less complicated step, where the women migrant workers need to go to a designated medical center, approved by the employer from the destination country. In having the medical check-up done, many a time, the women migrant workers become victims of extortion by deceitful independent migration intermediaries or intermediaries connected to a medical center where the medical reports they receive are not acceptable for visa processing. In some cases, leveraging the ignorance of women migrant workers, scamming takes place even when all medical parameters are all right. Sometimes, this ignorance is also leveraged by the informal intermediary connected to the PRAs in extorting the workers. Such instances lead to traveling with a false medical report, which may subsequently lead to deportation from the destination country and cause high financial losses.

For labour migration to Saudi Arabia, generally, the employer pays for the medical check-up as per the bilateral agreement between Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia. However, due to a lack of information about this provision, some women migrant workers end up paying for medical check-ups.

Step 7. Skills and Pre-departure Training

Skills acquisition and pre-departure training are two important components of migration clearance. Generally, BMET or DEMO designates a Technical Training Center (TTC) to a woman migrant worker for a two-month-long pre-departure training, mostly for domestic work. For job-specific skills acquisition, women migrant workers can also go for training at TTCs, and, at private training institutes, where the institutes are owned by PRAs of the Bangladesh Association for International Recruiting Agencies (BAIRA). Additionally, some NGOs like BRAC also provide training, which is approved by BMET and or National Skills Development Authority(NSDA)/ Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB). Even though the training is a mandatory requirement, through the collusion of informal intermediaries and the training facilities, many women migrant workers get certification without any or partial training. This leads to incidents of losing jobs in the destination country due to a lack of skills. It also leads to cost escalation due to unofficial charges for fake certification. In such cases, the training facilities receive money both from the employers and the women migrant workers. Many employers in destination countries are reluctant about the certification requirement as that allows them to pay lower wages. If employers were strict in getting skills certificates, the incidences of no-certificate travel or travel with fake certificate would reduce. NGOs and BMET have major roles to play in this stage. Through campaigns, they can alert the women migrant workers that false certification may lead to deportation, and make sure that these workers know that there is no fee for such training.

Step 8. BMET-Related Formalities [Migration Clearance]

An aspirant woman migrant worker can successfully complete this step at BMET without any trouble if she is confident and has adequate information and knowledge. However, lack of confidence and incomplete or wrong information leads to reliance on intermediaries at BMET, which leads to financial losses due to extortion.

Step 9. Immigration

After completion of all procedures and documentation, a woman migrant worker starts her journey out of the country, for the first time, being nervous. Knowing such vulnerability, an unscrupulous intermediary takes advantage and extorts her. Having false documentation provided by the intermediaries in earlier steps (any one or more of NID, work permit, medical report, visa) leads to the cancellation of the journey and arrest. Falling prey to the intermediary at the immigration point leads to extortion and harassment.

Step 10. Arrival

Upon arrival, a woman migrant worker is sometimes received by a representative of the employer. In certain cases, due to false documentation, a woman migrant worker may be stranded in the no man’s land and be barred from entering the destination country. Depending on the type of false document, she may be arrested and subsequently be ‘rescued’ from the no man’s land and taken to ‘possession’. As a result of such ‘rescue’, a woman migrant worker may end up working for the traffickers in an illegal job in the destination country or any other country. Such capture may also threaten their lives.

Step 11. Work

If a woman migrant worker is lucky, she is well received by an employer and facilitated for settling down with accommodation, registration, and proper job orientation. She may start working for the job she signed up for as per the contract with decent wages and benefits. However, there are other scenarios, where a woman migrant worker maybe with lesser luck or no luck at all. Sometimes it can be seen that the employer has changed the location of work, which is different from what was mentioned in the contract, with the partial fulfillment of contractual obligations. This may fall into the category of moderate risk.

It may also happen that the employer as per the contract does not exist or did not send the work permit, and the intermediary hands her over to a different employer with or without a contract. This is a high-risk situation, which may result in low wages, unsafe working conditions, unpaid overtime, and so on. In some other cases, it may also be seen that the woman migrant is forced to work illegally as her documents are not genuine. In such situations, these workers are risk of being caught, arrested, and deported. Due to such discrepancies in false expectations and harsh realities, a woman migrant worker may be forced to do an illicit job, and the low wage may lead to a severe debt burden and financial bankruptcy.

Often times, women workers become victim of systematic verbal and physical abuse, sexual harassment and abuse. In such cases, women migrant workers seek support of the labour wings at Bangladesh Mission. Some labour wings have shelter for women.

Step 12. Services and Facilities during work

Working within standard working hours allows a woman migrant worker to live a life where she can experience a good work life balance. It also allows her to replenish her energy for work. However, overtime is a common phenomenon for women migrant workers. While paid overtime with hours within the limit of law at least compensates for her sacrifice, it poses a low risk of being exploited. There are instances when women migrant workers are forced to work extra hours without any pay.

A woman migrant worker must have the following facilities and benefits at work:

- Possession of employment documents.

- Possession of phone for keeping connection with family and her safety network.

- Mobility outside the workspace for building and maintaining her social network.

- Access to Bangladesh Mission and Labour Wing for accessing services and emergencies.

- Paid sick leave.

- Paid annual leave.

- Health Insurance and access to healthcare.

- Access to reproductive health services.

- Maternity insurance.

- Access to legal aid and justice.

- Access to mental well-being support and service.

Step 13. Return

Women migrant workers may return home prematurely or after the completion of their contract. Whichever is the case, they must receive full payment of salary and other payables before leaving the job. Unfortunately, not all departures of women migrant workers are happy ones. The workers often return after being the victim of violence. Oftentimes, they have to pay for their return which results into financial bankruptcy. To prevent or protect the workers from falling victim to such situations, proper design and enforcement of provisions under the law may lead to a solution.

Since 2017 to 2022, total 705 women migrant workers died due to physical and sexual abuse. They take shelter before their departure from the destinations countries. BMET and NGOs try to facilitate legal aid and receipt of the due payment.

Step 14. Reintegration

Most of the women migrant workers, irrespective of the circumstances of return, are subject to stigmatization. Many returnee women workers are not well accepted by family and relatives. The community also excludes them in one way or another. This is a traumatic experience for them. The burden multiplies for those who return empty-handed and are the victim of violence. Lack of access to productive opportunities aggravates the situation for them.

After facing violence in a foreign land, a woman migrant worker requires a place to stay with dignity and support from her close ones. Instead, the family refuses to accept them. Cultural norms and beliefs lead to such stigmatization. A strong reintegration program for women migrant workers is essential for addressing these inhuman conditions.

Overall, women migrant workers face multiple challenges and risks at different stages of their migration journey. These include gender-based discrimination, exploitation, lack of access to information and services, and limited legal protection. It is essential to address these challenges through a gender-responsive approach that prioritizes the protection and empowerment of women migrant workers.

Author: Dr. Ananya Raihan and Nahin Mahfuz Seam

References

BMET. (2022, November 22). BMET. Retrieved from BMET: http://www.old.bmet.gov.bd/BMET/stattisticalDataAction

MoEWOE. (2021). Annual Report. Dhaka: Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment.

WEWB. (2022). Annual Report. Dhaka: Wage Earners’ Welfare Board.

World Bank (2022). Migration and Development Brief 37: Remittances Brave Global Headwinds. Special Focus: Climate Migration. New York: World Bank.